- Home

- Sophia Benoit

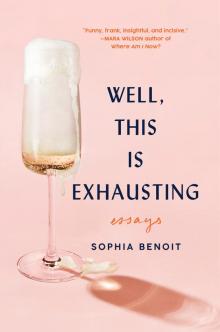

Well, This Is Exhausting Page 3

Well, This Is Exhausting Read online

Page 3

I remember thinking, That’s me. That’s me. That right there is me. My heart was racing because I was so thrilled to have an answer to why I ate everything that my friends didn’t like in their lunches, even after I’d eaten my own. Why at camp I got thirds and fourths from the buffet when no one else did. Why I saved my allowance to add money to my lunch account. It wasn’t something as poetic as loving food: I loved eating.

My mother, being both extremely compassionate and extremely worried, tried to force me into therapy, an exercise and healthy habits class for teens, and then, finally, a nutritionist’s office. She tried to appeal to me with everything she could think of. She told me stories of a friend of hers whose brother had lost his foot to diabetes—not because she thought that might sway me into eating healthier, but because she was terrified. She reminded me frequently how scared she was for me, but it’s not like you can just picture losing a foot every time you’re about to eat a whole bag of Reese’s and then put it down and walk away. I couldn’t. My mother’s imagined future for me at age twelve (diabetes) was about as real to me as my father’s imagined future for me (NASA physicist).

The dietician my mom sent me to lasted the longest. Possibly because we did what I already liked to do—talk about food. She missed the point entirely and probably cost my mother a lot of money and time away from work, but she would explain in buttery tones that matched her buttery blonde hair that if I simply swapped salami in my sandwiches for turkey, I’d be healthier. That was more fun to talk about than my parents’ divorce, which every other mental health professional thought was The Issue, but which I saw as normal since it had happened when I was two.

I think the dietician’s name was Becky, but she also looked exactly like my mom’s friend Becky, so I might just be transferring the name-memory over. Anyway, I didn’t really have a choice about visiting Becky; my mother believed strongly that sometimes you didn’t give kids an option not to do something. You just told them, “You’re going to therapy.” The moment I knew Becky was bullshit was when she tried to teach me about portion sizes of ketchup. BECKY!!!! ME EATING TWO SERVINGS OF KETCHUP INSTEAD OF ONE IS NOT THE ISSUE!!! It’s like when women’s magazines tell you that you can have a handful of almonds as a snack or a square of dark chocolate as a treat. Bitch, if I could stop at one square of chocolate we wouldn’t be here!

The problem was that no one knew what they were doing. My mother didn’t know how to help. Becky didn’t know how to help. The therapists I tried didn’t know how to help. I wasn’t sad or self-loathing (take that, Dr. S). They all refused to confront the problem I described to them. I wasn’t a binge eater so much as I was always eating and couldn’t stop. I wasn’t ignorant of healthy habits. I was simply addicted to eating, and every single time I started to eat, I began the struggle of when I’d be able to stop myself. Every meal was a binge. I wasn’t throwing up; I simply didn’t feel full ever. And even when I did eat healthily, I gained weight. I wasn’t eating my feelings, I was just eating everything.

I think about my childhood as a fat kid a lot, how I was parented and helped, corrected and cajoled, and what the adults could have done differently. I don’t know what the answer is. I asked a friend of mine who has struggled with weight her whole life, who was sent to fat camps and therapists, nutritionists and personal trainers, what she wishes her parents would have done. “Nothing.” That’s what she said, and she said it without pause. “I wish they’d done nothing. I’m still fat now, so clearly it didn’t help them reach their goal; all it did was ruin our relationship.” (We both agreed that while we could wish that now, had they really said or done nothing, we might still resent our parents.) There is no winning when your focus is on getting your child to lose weight, even if you feel certain that it’s for all the right, good, moral, healthy reasons.IV

What I know is this: As a fat person, I became my body and my body became everything. Not just to me, but for the people around me. It became uncomfortable for them to be around, and people like to fix or avoid discomfort. Being fat became part of my personality, it became all my worth. My body became a conversation piece and the metaphorical elephant in every room I entered, the breath held every time I sat on a too-small-for-me chair or tried on a top in a size that was not mine out of misguided hope. Eventually, at the behest of social acceptability, I shifted my obsession from eating to my body.

At some point, probably with the aesthetically obsessedV Greeks, we started conflating self and body. White cis men, of course, have mostly escaped that fusion. They’ve had enough nuanced narratives about them to fill the next two thousand years, and those narratives helped to establish that white men are more than just bodies. They are leaders, innovators, and intellectuals. They can sin and be forgiven because they are more than simply bodies. Everyone else… not so much.

For women, and minority women especially, as well as for non-cis people, bodies are given value only because (or whenever) they are consumable by the people in charge.VI That is what is at the core of our objections to objectification: I’m not for you. I’m not here to be jerked off to, fantasized about, yelled at on the street, derided, fucked, commented on, rated on a scale of one to ten, or assaulted when I decline any of the above. I’m mostly here on planet Earth to read crappy romance novels and get sick to my stomach from eating too much cookie dough,VII okay? Not for human consumption.

Of course, when you’re fourteen and eighty pounds heavier than your peers, you aren’t swayed by even the best self-love/self-worth arguments. You want your body to have worth like other kids’ bodies have worth. At least, I did. I was very, very, very, very exhausted from buying ugly one-piece swimsuits with skirts to hide as much of my body as possible while my friends got to buy two-pieces. I was exhausted from not being able to swap dresses after school dances. I was exhausted from never getting asked to dances in the first place. While hilarious now, I was burning with shame when my friends were all members of the Spice Girls for Halloween and I dressed up as a garden gnome. No one asks you to be in the Spice Girls—real or fake—when you’re two hundred pounds.

I was so starved for someone to like my body in any way, to pay it any positive attention. Once, in Mr. Drury’s algebra class—a class I was very happy to be in because my crush at the time was also in the class—said crush and a bunch of his friends sat in the back of the room and pointed at me “sneakily” and gestured to the fact that I had really big boobs. Which I did. Like really massive boobs. Big titters are great, and once you lose weight you lose weight from your boobs first and that’s how I know God is a fake bitch. Anyway, despite the fact that I also overheard their assessment of the rest of my body (gross), I was thrilled by the idea that they’d thought about my boobs at all.

* * *

Growing up, I lived in a town that boasted of having “the oldest football rivalry west of the Mississippi.” Think Friday Night Lights but in Missouri instead of Texas and with a lot fewer hot people. The point is that Friday nights revolved around high school football. Our field was surrounded on three sides by hills. Two of those three sides had bleachers where parents, the marching band, and high schoolers watched the games. But the middle schoolers spent the football games on The Hill.VIII The Hill was… well… a steep grassy hill with no seating and scant lighting, situated right behind the concession stand, an enclave that went mostly unpatrolled by authority figures.

I often didn’t go to The Hill, or football games in general. Partially, I didn’t go because I was with my dad every other weekend and couldn’t go those weekends. Partially, I didn’t go because watching football didn’t sound like fun. This was before I understood that we weren’t going to the game; we were going to the social event taking place next to the game. Anyway, on The Hill once I met a guy who was a grade older named Danny, a very, very popular hot guy who went to a different school—which somehow makes people more popular and more hot. A friend of mine who was also hot and popular, who was trying to be kind and show me around the football gam

e, introduced us. She told him my name and he replied with “Oh, I’ll remember that. I have a poster of a naked girl named Sophia on my wall with soapy titties.” Something in me must have come alive with the tiniest speck of male attention because, high on adrenaline, I replied, “Oh, me too.” Everyone loved it. At least, that’s how my memory re-creates this moment. More likely, a few people who had never talked to me before laughed politely. But I had finally—finally—found a loophole in being a nobody: I could be funny. That’s one thing people let you be when you’re a fat woman: you can be funny. Especially if you’re willing to make fun of yourself.

I wanted attention; I craved it. I tried being funny, because if you’re funny at least you’re getting some attention, but a lot of the time my “funny” was really mean or obnoxious. I knew I was often being mean or obnoxious but I couldn’t stop myself, because it was the only time I got attention from someone who wasn’t a teacher. And even bad attention is attention. I never got to text with a guy friend or even really have a guy friend, like the rest of my female friends did. I therefore never got invited to events by guys, only by the girls whom they’d invited. The few times guys talked directly to or with me that wasn’t a part of a group project, I tried to shock them and impress them. I’d take any dare, eat any disgusting food, say any profane thing I could think of, to hold their attention just a little bit longer.

Pretty much every woman who has ever grown up fat has stories like this, of feeling desperate of being overlooked. I’m not saying I had it the worst; I wasn’t the saddest or the most bullied teenage girl. In fact, I was mostly okay. But I have the markers of a fat female childhood both literal (stretch marks, which I ironically mostly got from losing and not gaining weight) and figurative (BODY DYSMORPHIA!!!). The bullshit part—well, one of about 24,048 bullshit parts—is that women are reminded that they’re only valuable if they’re young and if they’re thin, and if you spend your youth being fat, you’ve wasted all your good years, according to society. The years you might be worth something to someone else. And as much as I would have loved for fourteen-year-old me to get that you can also just be valuable to yourself and that’s “enough,” being beloved and cherished by ninth graders is a heady fucking drug.

Exactly the Woman I Thought I’d Be When I Grew Up

I thought I’d be married by now, not because I’m romantic, but because I thought I’d be divorced by now, and in order to be divorced, you must have at some point gotten married. Almost everyone in my family is on their second spouse. Some are up to their third or fourth. I always thought being divorced was glamorous, adult, sophisticated. What could be more grown-up than the end of a rocky marriage? To me, it was like owning a car or having a 401(k). I thought—I know, actually—that I would be a fabulous divorcée. I would go through it with wine and Fleetwood Mac albums. Which is not all that dissimilar from how I’ve gone through my normal life, now that I think about it. I would have close female friends come over and we’d shit-talk my ex-husband and do bad karaoke in my living room, and then a month later I’d start a brief albeit fulfilling affair with a slightly younger guy.

I assumed I would have lots of money. I know this is both a stupid assumption and an inevitable one after growing up in American Dream Land. You don’t fantasize about growing up and think, Hey, maybe I won’t be able to afford to go out to eat more than once a month and I’ll have to really budget for it. I thought I’d be able to walk into any store and purchase anything and everything I wanted; I assumed there would be shopping trips in my future where I came out of the mall arms laden with purchases. I also assumed I’d still be going to malls, so I was wrong about a lot of things, I suppose. I thought I’d have a nice apartment with one of those tobacco-brown leather couches from West Elm and a sunny balcony like all good Italian apartments have.

Speaking of Italians, I figured—hoped—that I’d speak fluent Italian, useful for my biannual months-long trips to my pied-à-terre in Siena. Also useful for my trysts with my rotating cast of Italian lovers. Sorry to use the word lovers, but there really aren’t enough good words for that. Am I supposed to say “fuck toy”? No, it’s crass. I’ll get a letter of complaint from one of my aunts about it, and I don’t need that headache.

I figured I would have bimonthly manicures. I don’t know; I thought nice adult ladies all had professionally maintained acrylic nails. I thought I’d wear perfume every day like my aunt Suzanne and that I would clean the house with a kerchief tied around my head like my aunt Karen.

I thought I would have lots of rings. Every adult woman I knew had lots of rings. Looking back, I think the women in my family just got engaged a lot and therefore owned a lot of redundant jewelry. Also, my aunt Patti is a jeweler, so perhaps that’s the source. Either way, I assumed my fingers would be decked out. As it stands, I think I own three rings that aren’t from Target, and I get too nervous to wear them anywhere.

I assumed that I’d live in New York City when I grew up. I listened to the Jay-Z and Alicia Keys song “Empire State of Mind” while working out in high school, preparing for my inevitable future in the Big Apple. New York, it seemed, was the place to be if you wanted to be glamorous and wear all black and rush to the subway holding a cup of coffee, which to me was the height of human adult experience. You know the opening of The Devil Wears Prada? Where the KT Tunstall song plays as a bunch of models get ready for the day? Of course you do. I assumed—not wanted, not desired, assumed—that my life would go like that. That I’d be rolling out of a bed (with a frame and a heavy white duvet), leaving a hot shirtless guy behind, telling him to let himself out as I put on heeled boots and rushed to catch the F train or something like that. I have no idea what the subway lines are called in New York and I don’t want to spend my life right now looking up which one would make the most sense to reference.

Everyone of style and substance that I could imagine lived in New York. By this I mean the characters from Nora Ephron movies, Nora Ephron herself, and Holly Golightly. I’ve seen the movie Breakfast at Tiffany’s only once or twice because it’s so glamorous that it makes me sad.I I can’t really explain it, but that movie makes me feel like someone beautiful died young. It feels the same way as Grace Kelly or Heath Ledger’s death, like something untouchable is gone. For Grace and Heath, the loss is about a person; for Breakfast at Tiffany’s it’s that I simply cannot ever be Audrey Hepburn, gliding around 1950s New York, gorgeous enough to get away with anything and naive enough to want to.

I feel this way about a lot of movies, people, stores, cities, etc. Breakfast at Tiffany’s isn’t even a particularly strong trigger for longing for me, other than, of course, the song “Moon River,” which could make even the most stoic person face the truth of mortality with sentimentality. I just used the movie as an example because we all know about that New York. And it’s a New York that I assumed I’d be a part of.

I felt I had seen enough of New York in the movies to understand what the deal was and the deal was this: walk the streets in a glamorous coat while on your phone, drinking expensive coffee. Occasionally attend a gallery opening (something no adult I know has ever done in real life). Vacation in a friend’s Hamptons mansion over the summer. Smoke on a fire escape. Hail a cab in a sequined dress. Cross the street openmouthed laughing with friends to get to a crowded bar. I needed no more information about New York; I got the deal.

For as long as I can remember I’ve known that I would grow up to be a famous actress.II Perhaps this started the day that my mother told me that Julia Roberts owned five horses and ten dogs. Ten dogs seems like a lot. Maybe it was ten horses and five dogs. I don’t even know if that number was true, or where my mother read that if it was. I just remember my mother telling me that and me thinking, Okay, being the highest-paid actress in America seems like the most reliable route to owning a bunch of dogs and horses, which was, of course, my ultimate goal at age six.

I suppose that I assumed I’d be on set for certain stretches of time. Or doing some acting

here and there. I definitely assumed I’d be hooking up with famous costars and attending the Oscars in gifted haute couture gowns. The only other career I could possibly fathom—and it took effort—was being in academia, but being the kind of professor who teaches abroad during the summer (international travel is clearly a theme for me), and who sleeps with the married department chair (sex also clearly being a theme for me). Mostly, though, I assumed I would be famous or at least somewhat wealthy, which is basically the same thing.

My idea of fame was mostly that you were in magazines, a medium I venerated. I practiced my interview answers frequently. I also figured I would be going to high-society parties in apartments with crown molding and wainscoting and built-in bookcases. Apartments with nine-foot ceilings and kitchens hidden away because my God who goes into their own kitchen? I didn’t expect myself to be so ungodly rich as to own an apartment like that in New York, but I did certainly think my friends or acquaintances would be. Going to a sumptuous party once a month or so seemed doable. Likely, even. When I traveled, I expected to stay in hotels that provided robes.

One of the hardest presuppositions of mine to let go of was the idea that as an adult I would be extremely fit and incredibly hot. I did not, for some reason, assume that the stretch marks of my youth would carry over into the fantastical world of adulthood. I thought I would have long, lean legs that I showed off in miniskirts. (I also assumed I would know how to get out of cars gracefully without showing off my undergarments, something I’m still mediocre at.) I did not imagine working out or eating with any level of discipline, really. I just assumed I would be, well, someone else entirely, and that included my body.

Well, This Is Exhausting

Well, This Is Exhausting