- Home

- Sophia Benoit

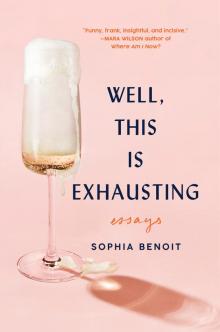

Well, This Is Exhausting

Well, This Is Exhausting Read online

Thank you for downloading this Simon & Schuster ebook.

Get a FREE ebook when you join our mailing list. Plus, get updates on new releases, deals, recommended reads, and more from Simon & Schuster. Click below to sign up and see terms and conditions.

CLICK HERE TO SIGN UP

Already a subscriber? Provide your email again so we can register this ebook and send you more of what you like to read. You will continue to receive exclusive offers in your inbox.

For Mom and Papa.

I know I don’t say this enough: this is all your fault.

Contents

Introduction

SECTION ONE, in which I try really hard to be a good kid for my parents, miss out on a normal youth because I was fat, and then date someone who sucks.

Bless You, Brendan Fraser

Too Many Servings of Ketchup

Exactly the Woman I Thought I’d Be When I Grew Up

How to Use Your Parents’ Divorce to Get Kicked Out of Gym Class

“I’m Difficult.” —Sally Albright (but Really Nora Ephron)

The Tyranny of Great Expectations

What I Wouldn’t Give to Be a Teen in a Coke Ad

Things I Want My Little Sisters to Know, Which I Will Write Here Since They Aren’t Texting Me Back Right Now

The Idea Is to Look Like an Idiot

How to Hate Yourself Enough That Men Will Like You (but Not So Much That They’ll Be Turned Off)

SECTION TWO, in which I try really hard to impress shitty men, discover Skinnygirl piña colada mix, and learn how to do eye makeup.

One Time I Listened to the Sara Bareilles Song “Brave” to Work Up the Courage to Ask a Guy Out (I’m Embarrassed for Me Too)

Everything I’ve Ever Done to Impress Men (and How Successful Each Was)

Cracking Open an Ice-Cold Bud Light

I’m Not Doing Zumba with You

Good Coffee and Why Pierce Brosnan’s Voice in Mamma Mia! Is Perfectly Fine

I’m Pretty Sure My Insatiable Capacity for Desire Stems from the Scholastic Book Fair

Everyone I’ve Ever Wanted to Like Me

The Greatest Joy on Earth Is Getting Ready to Go Out

Adventures at a Lesser Marriott

SECTION THREE, in which I get very tired of trying so hard, realize I was wrong about almost everything, and save my boyfriend’s life.

Kirkwood, Missouri

The Internet Made Me a Better Person

Imaginary Dinner Party

Not to Be Cliché, but I’m Going to Talk About My Vagina (and Tits)

There Were Two Different Songs Called “Miss Independent” in the 2000s. Why Is No One Talking About This?

How Exactly to Be Likable

Sorry, Dove, but I Am Never Going to Love My Body

How to Be the Life of the Party in 28 Easy Steps

I Check to Make Sure My Boyfriend Is Still Breathing When He’s Sleeping

A Short Letter to Responsible People

Riding Shotgun with My Hair Undone in the Front Seat of Margaux’s Truck

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Notes

“It’s a decision a girl’s gotta make early in life, if she’s gonna be a nice girl or a cunt.”

—Tony Manero, Saturday Night Fever (1977)

“I’m gonna be real with you, 90 percent of the time when there’s a quote at the beginning of the book, it’s v[ery] esoteric and it makes no fucking sense and doesn’t seem to relate to the book at all—and even if it did, I haven’t read the book yet so what the shit do I know.”

—Sophia Benoit, Twitter (2020)

Introduction

When I was about six or seven years old, my dad gifted me The Phantom Tollbooth. This was thrilling because (a) gifts from dads are always thrilling and (b) it was a book. I was a huge readerI and I felt very ready to dive into this Important and Grown-Up chapter book. I began reading almost immediately. At least, I tried to. There was one huge problem: The Phantom Tollbooth was boring as shiiiiit. Every few months I would open the book up again and try and try to get into it. My older sister, Lena, had already read it and loved it. My dad had recommended it. I couldn’t understand what I was missing. I felt stupid and embarrassed for not liking the book, for not getting the book. The back cover said it was about a bored white boy on a journey, which is what approximately 82 percent of kids’ books were about until the ’90s, but despite reading and rereading the synopsis, I couldn’t figure out what the hell was happening in the story.

I put the book aside and went back to The Baby-Sitters Club, but it remained my white whale. I held out hope that someday I would be like Lena and Papa and I would understand The Phantom Tollbooth. A year or two went by.II I finally decided to try again. I cracked open the book, flipped past the dedication, and landed on a page titled “Introduction,” and I started to read it again, except this time I realized something. Something important. I realized what the hell an introduction is. I had been under the assumption that the introduction was part of the story. I had never before read a book that had to introduce itself. I had been trying and trying to get into this book, thinking that this was chapter one; meanwhile, I was reading a bone-dry introduction from the author about his time in the military and how he’d asked some other guy, Jules Feiffer, to do the illustrations for the book. I just didn’t realize that an introduction was a whole separate thing. I know!!! Dumb bitch alert!!! Once I skipped ahead and got to the actual story, I loved The Phantom Tollbooth.

From that point on, I had quite the vendetta against introductions. For many, many years I simply leapfrogged right over them, assuming, often rightfully, that I wouldn’t need the information therewithin. Then I grew up some more and figured reading the intro was the right thing to do, so I forced myself to. Some of them are still bone-dry. Sometimes authors use the intro to just lay out everything you’re going to learn in the book and then what’s the point of even reading the book? The best introduction in my mind would be one that shares a juicy piece of gossip or drama, although authors don’t usually do that. On the whole, I think we could live without intros.

Well, guess what? I’m finally publishing my own book and I’m going to do what I want. No one can stop me!III I’m a rascal! And also my editor explicitly told me: “You have to have an introduction.” So now I just have to transition from this meta diatribe against introductions into the real introduction, where I outline the Big Themes, reminisce about my military career, and tell a raucous tale of how Jules Feiffer declined to do illustrations for this book.

Perhaps because of my historically anti-intro stance, I was a bit lost on how to actually introduce my own book, so I made a semi-frantic call to my aforementioned editor and said, “Okay, so… be honest… what the fuck am I supposed to write?” (Note: it is not the job of the editor to tell you what to write.) And she was very kindly like, “The introduction should serve as a meditation on who you are and why you wrote this book.” So let’s do that. I think I was supposed to be more subtle than this—in fact, my editor explicitly was like, “Don’t come right out and say it”—but if this part is in the book you’re holding, I can assume that my editor felt she’d allow this to pass, that there were bigger fish to fry. Someone had to talk me out of titling the book The Da Vinci Code 2: Guess What, You Can Name Your Book Anything, so you can imagine there was a lot of work to be done behind the scenes.

About five years ago, when I first set out to write this book, most of the funny nonfiction books I’d read by women—of which I have read many—were chockablock full of women being a mess. They were stories of disastrous one-night stands, raucous parties with minor celebrities, “charming” (insanely privileged) tales of twentys

omething white women getting fired from shitty jobs and moving back home for a month before getting offered a salaried gig with health insurance in the big city. Everyone, I felt, had a story about a bad breakup, mountains of cocaine, a sketchy hostel on a European vacation, the alienation of people you love, and the morning-after pill; sometimes that was all one story. To me, this was the template. Take your craziest, funniest stories, the stories that painted you in a kind-of-bad-but-not-too-bad light, put ’em in a bag, shake ’em up, and you’ve got a memoir. You’re a person to whom things have happened.

I don’t have those stories.

A couple of years ago, at my friend Tam’s house, her cool artist-musician friends were planning that they were going to do cocaine at Tam’s bachelorette party the next week, where we were all going to get together and go to a Chippendales show.IV Someone took an informal poll of who was going to do coke, and they asked me if I was going to join and I said no because I’m a little baby and I had never seen cocaine in real life before let alone done it, and they kept encouraging me to try coke for the first time next week before we went to the show and I got so overwhelmed that I cried.

I cried when offered cocaine a week in advance.

And somehow I spent years trying to write a book about all the funny, crazy, wild things that happened to me. The truth is, those things didn’t happen, because the reality is: I am a careful person. I weigh risks, and when in doubt, I err on the side of staying home and watching To All the Boys I’ve Loved Before for the thirty-eighth time. Once I finally admitted to myself that I’m not exactly a Wild Fun Person and therefore cannot write a book about being a Wild Fun Person, a lot of things opened up. I realized the very obvious concept: You Should Write the Truth, Sophia, Not What You Want the Truth to Be. I realized I had all of these actual stories and viewpoints and philosophies inside that I had been thinking (complaining) about for years and years. Most of what they amounted to is this: no matter how good you are, no matter how well you behave, no matter how few risks you take, you will get hurt. You’ll feel left out. You’ll be lonely. You’ll wish you had more friends as an adult. You’ll get acne on your chin. You’ll feel like your boss hates you. You’ll get a bunch of parking tickets. You’ll never get it right.

You can’t beat the system just by behaving, and society sure has a whole lot of ideas about how you should behave if you happen to be a woman—and even stronger and more restrictive prescriptions if you’re also part of any other marginalized community. No matter how closely you follow the guidelines, how stringently you appeal to the straight cis male gaze, you will not win. Look at Anne Hathaway, for example: she has it all.V She’s done everything right. She’s rich, has perfect teeth, can walk in heels, has won an Oscar, has been in a Nancy Meyers film, is friends with Emily Blunt, is the Queen of Genovia and Catwoman, and looks great with short hair. (My only knock on her is that she named one of her sons Jonathan and then the next son Jack, which is a nickname for Jonathan.) After she won an Academy Award a lot of people just started hating her for all kinds of strange reasons: for being too into acting, for trying too hard, for seeming insincere in her humility. Some people simply hated her for no discernible reason at all. Some people still hate her! And if Anne Hathaway is an object of this much baseless criticism, then you know the rest of us are.

I felt pressure in my life to be more fun, to write a book that had more wild stories. Stories that included risk and danger and unexpected hijinks. Stories that would have made me look bad if they didn’t make me look so cool. Long before I was trying to mine my life for stories that would make me seem fun, I felt pressure to be thinner. I felt pressure to be quieter. I felt pressure to not be such a know-it-all. I felt pressure to drink, to dance, to be easy to talk to and hard to get into bed.VI I felt pressure to like good TV and hide the romance novels I read behind other, more “intellectual” books on my shelf. I felt pressure to be a good daughter, a good student, a good girlfriend, a good employee. And I tried really hard, because what if all it takes to be like Anne Hathaway is trying really, really hard to please everyone around you?

Well, spoiler: it did not work. I am not succeeding on almost any front that Anne Hathaway is doing well in; I don’t even have a garbage disposal or air-conditioning in my apartment. I tried really hard to please other people and all I got was tired.VII Maybe you’ve felt the same way—like you have tried really hard and been good and it hasn’t always paid off and you’re not always sure what the point of trying that hard is or who you’re even trying for anymore. I feel you. This is the story of a girl named Lucky. Just kidding,VIII but it is the story, loosely, of how I went from being an anxious Goody Two-shoes kid to an anxious insecure wannabe-slutty college student to a still-anxious but now very tired adult who gave up on pleasing people so much. It’s the story of how I learned how to be good for myself rather than for other people. A little bit. I’m not doing perfectly; let’s not get crazy.

SECTION ONE,

in which I try really hard to be a good kid for my parents, miss out on a normal youth because I was fat, and then date someone who sucks.

Bless You, Brendan Fraser

Like most people, I experienced my sexual awakening during the horse scene of the award-nominated film George of the Jungle (1997). If you don’t know the scene, let me explain: Leslie Mann takes Brendan Fraser—whose body is BANGIN’ HOT and whose long hair is LUSTROUS—to her ritzy engagement party to another man, Thomas Haden Church. George/Brendan is wearing an impeccably tailored (for the ’90s) suit, which is already enough to get anyone’s engine (vagina) going, but then he leaves the party to go hang out outside with animals (relatable as hell). He climbs into a pen with some horses that are on the property, because rich people always have horses, and he starts running around with them like he’s in a horny perfume ad. Naturally, all the hot single women at the party come watch this sexy display. A couple of men scoff and ask, “What is it with chicks and horses?” which is a valid, if sexist, observation. I maintain this is the first time in cinema that women’s sexuality was fully understood. It can be no coincidence that Sex and the City premiered the following year, building off what GotJ had already laid down.

I was only about four or five when I first saw this movie, and yes, that does feel young for me to have my sexual awakening, but it’s never too early to get horny. After I saw this magnificent film, I was destined to be thirsty forevermore. Actually, I don’t know how much it has to do with Brendan Fraser; I was just a horny kid. Strictly speaking, when GotJ came out, I was already getting in trouble for masturbating during nap time at preschool, even though I had no idea what I was doing. I was just humping things constantly, which is a fairly normal thing for kids to do, it turns out. I didn’t know that, though. It’s not like you can tell a four-year-old that it’s normal to want to hump things but that they can’t because of society’s complex, horrid relationship with sex. I eventually got the message that I wasn’t supposed to be jerking off in public, even though no one really explained it to me. What I did glean from the adults around me was that there was supposed to be shame around whatever it was that I did before bed every night; I often tried to quit. I would go weeks or months, proud of myself for having given up my nightly ritual, only to relapse. This was not long after Dr. Joycelyn Elders, the first Black surgeon general of the United States, was asked to resign after saying that masturbation was “part of human sexuality.” In 1994, by Bill Clinton. The famously sexually appropriate president.

When I was about thirteen, my mom sat me down for the number one most mortifying conversation of my life and informed me that what I had been doing every night since I was a child was masturbating and that that’s what sex felt like. I, of course, was fucking pissed. That’s it? That’s what sex is like? What a total scam! Here I thought I had another cool thing to experience on the horizon, but nope! I’d already been doing it since preschool. Seeing my disappointment at this, my mother assured me that sex would be so much better because it was w

ith another person, and I rolled my eyes and was like, Yeah, fucking right, Mom. There’s no way anyone knows how to do this better than I do. And for the most part, I have been right about that. Sex has rarely been better—or at least more reliable or easier—than masturbating, in my personal experience. Another total scam.

I didn’t grow up in a household that shunned sexuality. There used to be a magazine rack at my dad’s house that held dozens of magazines; I believe my dad and stepmom had it custom-made since my dad subscribed to so many. There was one magazine that was on the rack that I loved. It had Tyra Banks on the cover, topless, with her long hair covering her boobs. The cover said, “Tyra, please pull back your hair.” I would often sneak into the living room when no one was around to look at it. I remember a pinup calendar in my dad’s basement office that featured a naked woman wrapped in cellophane for December (she’s an object—get it?). I remember December because that calendar stayed up on the wall in the basement for years after my father moved his office up to the attic. Only once did I work up the courage to take the calendar off the wall and peek at the other months before setting it back to December.

My mother, for her part, was even less of a prude. In a hyperrational move typical of her, my mom never minded sex scenes in movies, as long as there wasn’t violence; at age ten I saw my first R-rated movie, Love Actually, where we see quite a bit of Martin Freeman and Joanna Page (at least there are no guns). When my older sister Lena and I asked what sex was when I was about six, Mom calmly explained (in an age-appropriate way) about bodies and babies. She never found sex repulsive or embarrassing. She wasn’t crossing weird boundaries with Lena and me or anything; she was just clear that safe sex isn’t a big deal.

No one in my house was selling the lie that sex ought to be shameful, but I still got the message anyway. You can’t live in America and not get the message that sex is wrong. I got it from the way movies were screened for children and what we were allowed to talk about at recess, and most of all, I think, I understood sex is shameful because of the general silence and discomfort around the topic. Children have a keen sense of what is Not to Be Discussed.

Well, This Is Exhausting

Well, This Is Exhausting